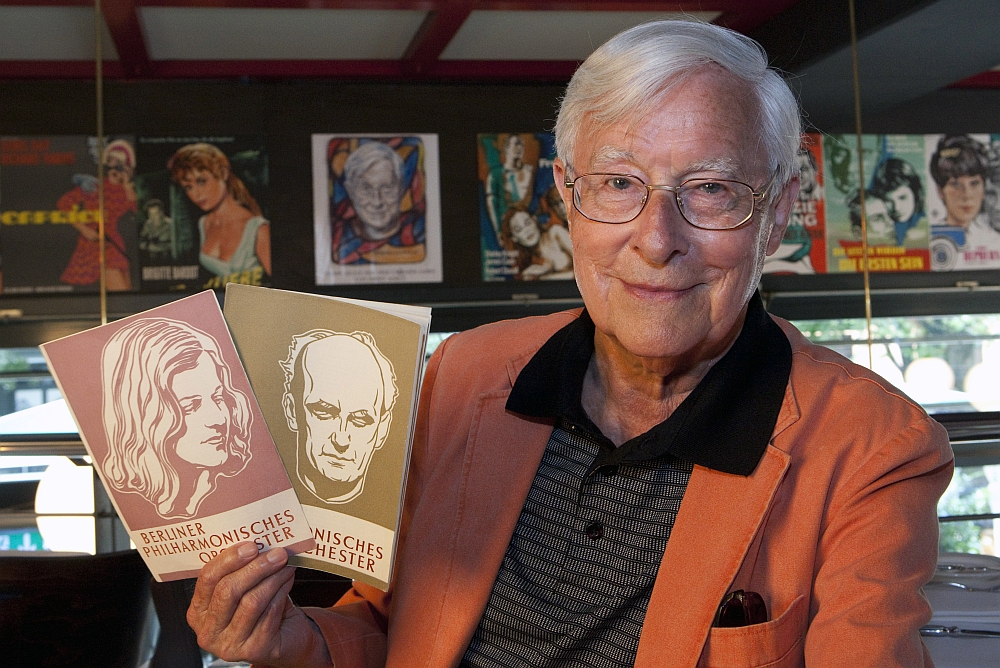

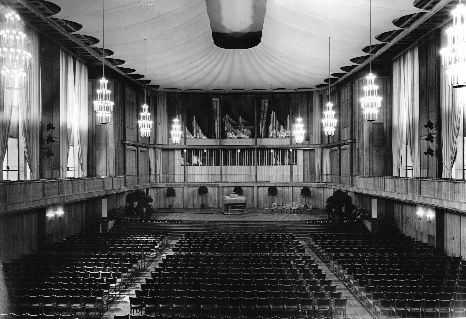

This programme is one of a set of eight acquired by the SWF from the Berlin Philharmonic concert seasons of 1940/41 to 1943/44. A few general observations before we open them. This was wartime, and thus a period of restrictions, but the quality of the documents is surprising: cardboard covers with two-colour printing, at least one photograph, analyses of the works — and no reference to the government of the day; it is as though we were in a world without the swastika. Finally, some programmes include a section on “Philharmonic News”, or announcements of forthcoming concerts, which enable us to follow the orchestra’s activities. And we might note that this concert was given three times, and hence to a total of more than five thousand listeners!!

Here we have a somewhat untypical programme.

The first things we see on opening it are the tributes to Mozart from famous names, and on the reverse is a portrait of Wolfgang Amadeus — according to the back cover, a pastel by Tilgner from around 1786.(1) Why? It was November 1941, and this was the beginning of the “advent calendar” of tributes to Mozart for the 150th anniversary of his death.

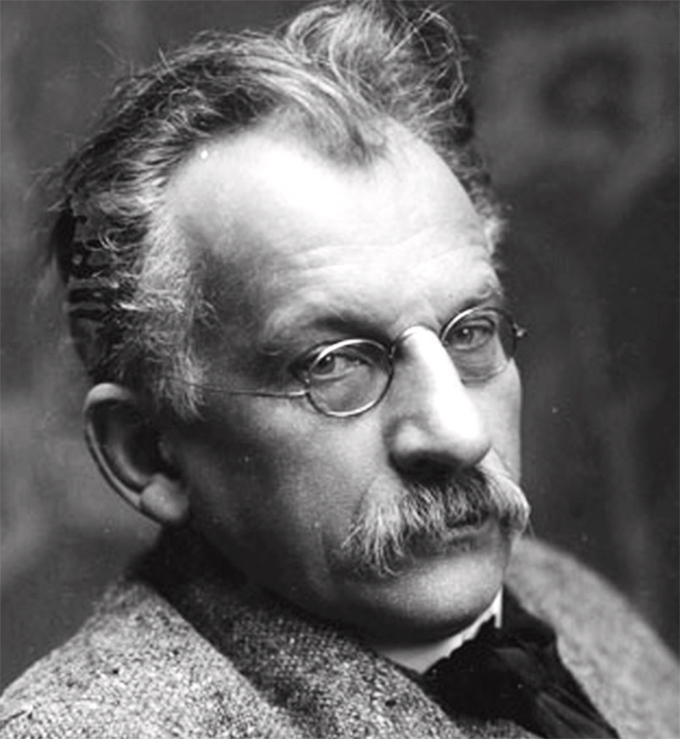

It was perhaps for this reason that Furtwängler programmed a work related to the Salzburg master by Max Reger, a composer whom he respected and whom he had served well with the baton. Of all Reger’s works in his repertoire, including the Beethoven Variations and the Boecklin Suite, the Mozart Variations appeared the most frequently in his programmes. Curiously, however, he would not conduct a note of Reger after his return in 1947. (For more information, we refer the reader to the study Furtwängler and Reger, available on the SWF website.)

The same is true of Dvorak’s New World Symphony, which he conducted less often than might have been expected given the work’s popularity. This was also the only one of the Czech composer’s symphonies that he performed, alongside rare performances of the cello and violin concertos. And here again, this great romantic disappeared from his programmes after 1944.

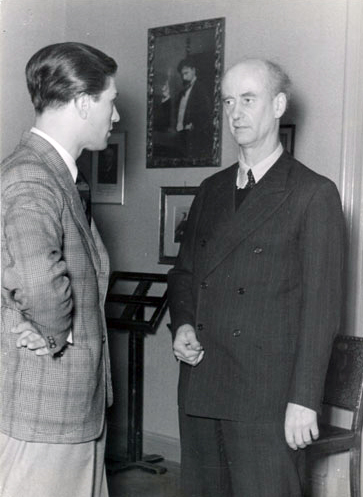

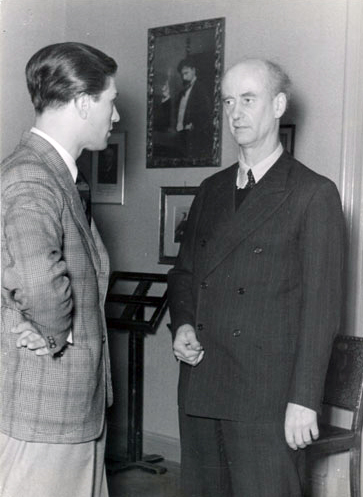

Between these two works, Furtwängler offered a very young musician a prized opportunity to present himself alone: Gerhard Taschner, whom he had just engaged in the post of Konzertmeister at the Philharmonie. Such noble gestures are not characteristic of all great conductors! In paying him the tribute he deserves, we can only regret that this violin prodigy’s difficult character and psychological instability deprived him of the post-war career which he should have enjoyed. The necessarily short biography of the newcomer is sketched on the penultimate page. Among the masters mentioned as the apprentice’s trainers, the self-censoring editor omitted a name that would then have been unwelcome, that of Bronislaw Huberman… And what the programme does not say is that this brilliant 20-year-old was the subject of a competing and more remunerative offer of the same position at the Staatskapelle Berlin, from its conductor Herbert von Karajan.

On the back of the booklet are details of forthcoming programmes. On 16 December Furtwängler had planned to play Mozart’s Concerto no 27, conducting from the keyboard. In the end, however, he opted to give the “Gran Partita” Serenade, with thirteen members of his Philharmoniker.

(1). The attribution to Tilgner is strange! Viktor Tilgner (1844-1896) did indeed pay homage to Mozart, but with the famous sculpture of the Mozart monument in Vienna.