On 4 April 1948 Furtwängler wrote to Ludwig Curtius that he had just “come back into contact with the Anglo-Saxon world under conditions which were outwardly far from adequate”. Adequate or not, the circumstances were certainly extraordinary. He was the first non-exiled German conductor to perform in Britain after the Second World War (the Austrian Clemens Krauss had visited in 1947 with the Vienna State Opera). In 1948 he made four visits, giving 21 concerts with four different orchestras, of which eight were broadcast by the BBC in whole or part. He also conducted the only complete cycle of Beethoven symphonies that he ever gave, with the Eroica even being televised; had a lengthy radio discussion with the left-wing journalist H N Brailsford; and recorded for both HMV and Decca.

In 1938 Furtwängler told Fred Gaisberg that his recent experience with the London Philharmonic had convinced him that he could obtain playing from them comparable with that of the Berlin Philharmonic. But during this first visit of 1948, lasting four weeks, he conducted a London Philharmonic which had lost its founder Beecham and had not yet had its fortunes revived by Boult. More positively, however, any concerns he might have felt about his reception, in what had so recently been an enemy country, must have been dispelled when the orchestra spontaneously stood and applauded on his arrival [i].

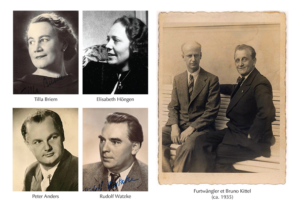

The rehearsal demands would have been considerable. The programmes for their ten concerts encompassed all four Brahms symphonies and Beethoven’s Seventh and Ninth, plus thirteen other works, most of which were played only once during the series. The first concert included Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a theme of Tallis (which he had given in Germany in the 1920s), while, as the programme shows, Haydn’s “Clock” Symphony and Sibelius’s En Saga were given in a benefit concert for the LPO pension fund. In addition to all this he recorded Brahms’s Second Symphony with the LPO and, in his first encounter with the Philharmonia, the Immolation scene from Götterdämmerung with Flagstad.

The visit included concerts in Birmingham and Leicester, and — perhaps more surprisingly — the London suburbs of Watford and Wimbledon, which would be lucky to see a star conductor today. Many different types of music were played at Watford Town Hall, but today it is remembered mainly as the scene of numerous classical studio recordings. The programme was a characteristic combination of established German masterpieces and more recent and challenging works. Furtwängler had little enthusiasm for Mahler, but championed a composer whose work was then little known in Britain; many in the Watford audience would have heard Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (billed under its standard English title “Songs of a Wayfarer”) for the first time. Eugenia Zareska was soon to appear at Covent Garden, later settling in London and taking British citizenship.

The (mostly anonymous) reviews compiled by John Squire in his 1985 study Furtwängler and Great Britain [ii] make no mention of the recent war; one’s impression is that the musical establishment was just relieved to return to peacetime conditions and looking to the future. Musically, Furtwängler divided opinions in 1948 much as he had always done in Britain, where some saw him as excessively subjective. But the Music Review was on his side, finding that “his chief characteristic… remains unchanged: his power of seeing a piece of music whole as a microcosm of human experience — though his executive abilities were not always equal to inducing the London Philharmonic to give full effect to his ideas”.

Eugenia Zareska

[i] Recounted by Robert Meyer (1920-2016), double-bassist in the LPO and later the Philharmonia, in his “Musical Reminiscences”.

See: https://robertmeyer.wordpress.com/2007/04/20/wilhem-furtwangler-conductor

[ii] Wilhelm Furtwängler Society UK, 1985