Concert in Vienna, 13 February 1949

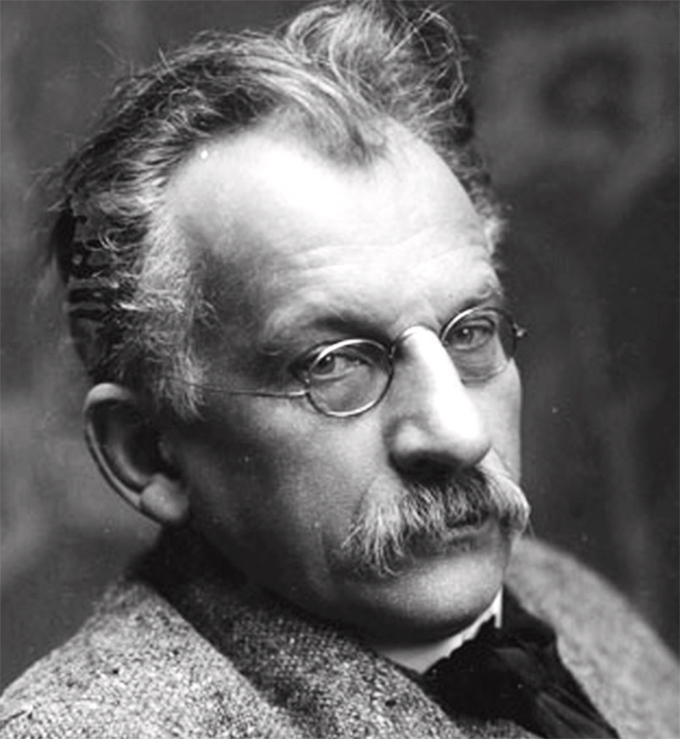

Some see Pfitzner as the last link in a musical chain dating back to Bach. Holding the whole evolution of music in the twentieth century in contempt, he saw himself as the last line of defence against a barbarism advancing both from abroad — he was an absolute xenophobe — and from within his own "camp". History has shown him uncompromising and all of a piece: inflexible, cantankerous, bilious, the enemy of everything and everyone, even managing to put the Nazis’ backs up. Some of his works have survived, but not this "Rose from the Garden of Love”, his second opera, with its impossible libretto and incongruous musical style, which never travelled beyond the borders of his country and is now largely forgotten even there. In conducting an excerpt from this work, one wonders whether Furtwängler was acting out of artistic conviction or merely a kind of filial piety.

On the other hand, he certainly conducted Bruckner's Fifth with passion, particularly since the Haas edition had revealed the true stature of this work — above all the Finale. In this connection, the commentary in the programme includes a myth of sorts which was still current at the time. In the instrumentation of the orchestra, the writer lists doubled brass for the Finale, reinforcements which were not originally planned but which most conductors have adopted. In those days these extra instruments were often placed above the rest of the orchestra in the organ gallery, leading to allusions to the twelve Apostles. Furtwängler might perhaps have followed this fashion; in a letter to the Vienna Philharmonic itself, he asks that these additional brass forces be placed "within" the orchestra. In reality we should disregard this romantic perspective: the brass is doubled simply because the players face such demands that their lips are too tired for the Finale, and especially for its colossal closing chorale.