The event took place in Berlin, on the evening of February 13, 1942, at Bernburgerstrasse 22a/23, i.e. at the Berlin Philharmonie. Furtwängler conducted his Philharmonic there during a special concert given for the benefit of Aid for Elderly Artists, in the presence of the actress Ida Wüst, president of that organisation. The programme was to have included the Variations on a Theme of Mozart by Reger, which had been given two months earlier in the subscription concert series. “Was to have included…” because at the last moment — well, look at the programme.

As the conductor raised his baton to start Till Eulenspiegel, the second item in the altered programme, a gentleman rose from his seat, no 31 in row 24, and shouted: “What about Max Reger, Mr Furtwängler?”. This intervention disturbed people nearby, and a muttering began. Furtwängler, after half-turning around, decided to begin.

This is how the scene was reported in the DAZ (Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, the most important of the German daily newspapers) by a certain Dr W. Theobald, who finished by deploring the failure of the hall staff of to intervene and put an stop to this inappropriate interruption.

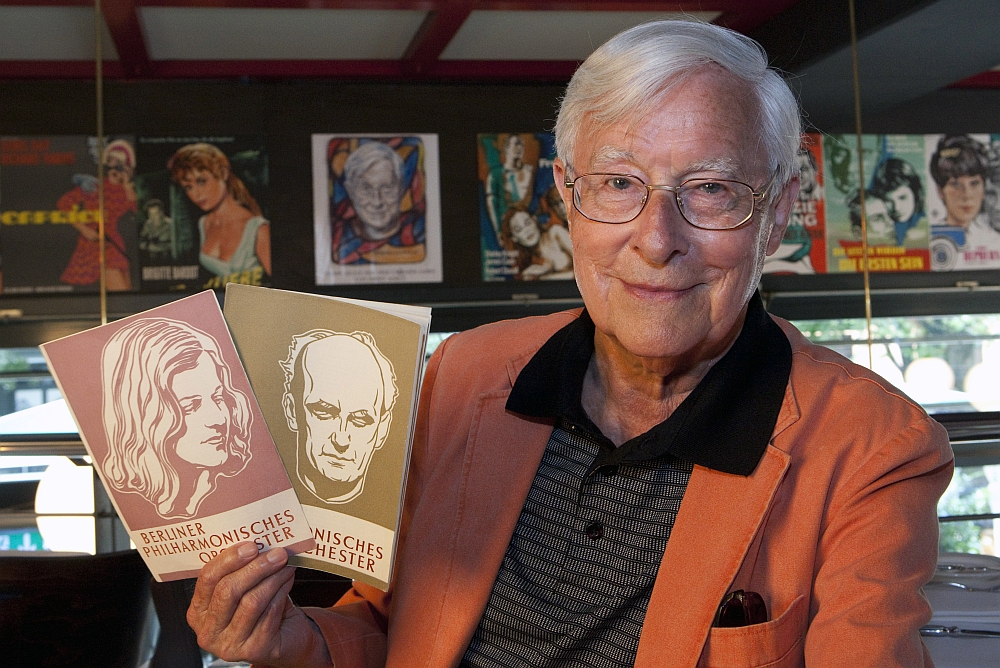

The matter snowballed when the DAZ published a letter from Mr. Hinnrichs, a professor of music and the cause of the scandal. He explained that he paid 6 Reichsmarks for his seat, 0.40 RM for the cloakroom (this was February…) and 0.50 RM for the programme. He had been waiting impatiently for weeks to hear Max Reger’s Variations on a Theme of Mozart, performances of which he found regrettably rare. And then he was robbed of this satisfaction, and it was only on the evening of the concert that the change took place — as was shown by the presence of a loose sheet slipped into the programme. So why this change? A sick flautist? Was the fourth horn unavailable? And why the lack of information for the public? And, he says, contrary to what has been reported, many people in the audience had expressed their appreciation of his action during the interval.

The DAZ subsequently received numerous letters both for and against, and printed two responses.

The first was from Furtwängler, who while praising Mr. Hinnrichs’ passion for music and this work in particular, and understanding his disappointment, nevertheless deplored the manner in which he chose to manifest it.

It was the Intendant of the BPO, Gerhardt von Westerman, who explained the change of programme. If one of the instrumentalists had been unavailable, there would of course have been a replacement. In reality, however, the orchestra had just returned from a tour of the Scandinavian countries, and the journey from Copenhagen to Berlin did not go as planned, with 32 hours of travel plus some hours overnight in the railway station in Hamburg. The instruments themselves did not arrive at the Philharmonie until very late; it was no longer possible to rehearse the planned programme, and the management had no choice but to present works which had been well rehearsed during the tour.